Photo credit: PicturePartners / Envato Elements

George A. Miller wrote the groundbreaking book The Psychology of Communications in the 1950s, but his work echoes down the decades and into UX concepts to this day. For me, the most interesting of the findings he describes in that book is from his research paper entitled The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information. It describes how he proved that at any given moment, the typical human brain can learn and recall about seven chunks of information, plus or minus two. For example, if I ask you to memorize a string of numbers of ten numbers like 15643934812, you may struggle to do that, but if it’s chunked, it’s much easier: 1 564-393-4812. Chunking is now a common concept in information organization, but it was Miller who first coined the term when describing this 7 +/- 2 concept.

Miller’s interest may have been sparked by the 19c. economist and logician William Stanley Jevons, who he mentions in his book. Jevons observed that if he threw a random number of beans in a box, he could instantly state the quantity if there were four or five, but if there were ten beans, he always had to to count them to be sure. Miller went on to show though his research that around seven items is that critical threshold up to which we can just “grok” an information set.

Applying Miller’s “Magic of Seven” Law

The “magic of seven” has obvious application in UX design. We might choose to organizing our information architecture to limit the number of choices in each of our navigation menus, or the number of radio buttons in a group. If users need to hold choices in their mind between pages of our site, or need to pick from a list of options, we might consider chunking up the options into groups so each is a maximum of six or seven.

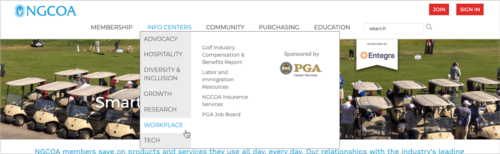

This megamenu shows how the large number of navigation options offered are organized into a hierarchy with no more than seven choices at each level.

Credit: National Golf Course Owner’s Association – used with permission.

Of course, sometimes you may decide to group ten or more items, but be aware the further you go above seven or so, the time and effort needed to make a choice disproportionately increases.

Combine with Hick’s Law – choices are good, choices are bad

Miller’s Law of 7 +/- 2 has a companion in Hick’s Law, which predicts that the time and the effort it takes to make a decision increases with the number of options. There’s even a formula you can use to determine exactly how much time is needed based on the number of items and other factors. Together, Miller’s Law and Hick’s Law give sound research and guidance around keeping lists of options short and reducing the number of options we present to the user at any point in their journey.

The Inevitability of Long Lists

Of course, laws are meant to be broken under the right circumstances, and there are times when long lists are inevitable and even desirable: for example, menus in online shopping forms that enable selection of a US state or a country name must, by the size of the sets, have more that seven choices. And, as Katie Sherman at Nielson Norman Group explains in the video Hick’s Law: Designing Long Menu Lists, there are two criteria for creating long list of items like this: 1) the list is organized, typically alphabetically, and 2) it’s a list the user will be familiar with. And of course, state and country lists meet these criteria. That menu listing your company’s 17 products, not so much.

In short, keep it short.

The first step towards working within the bounds of what your users can easily grasp and remember is to limit to number of options in any “choice group”. That can be achieved by either grouping options into smaller, named and logical sets, or spread them across multiple pages – years of research sessions have taught me that users would rather click a few times while making a series of quick decisions than sit on one screen trying to take in the all the options. The less frequently that a particular user might use the system (for example, they visit once a year to select their health benefits), the more you should chunk the task into smaller steps, for easier comprehension and that all important sense of forward progress.

At some point, it can be better to let the user search than select but, of course, searching requires the user to know to some extent what they are looking for.

A final thought here is that sometimes we don’t need all those choices in the first place. Ask yourself: can we focus in on only the key user needs, and thereby reduce the number of options that are offered? When creating architecture, or menus and forms – anywhere you are organizing groups of items – ask to yourself: what is the user’s task here, their central problem we are solving? Is there anything here that doesn’t help the user complete this task? You may be surprised to find you don’t need so many options after all.

Citations:

The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information![]() ,” Psychological Review, Vol. 63, No. 2, 81-97 published 1955

,” Psychological Review, Vol. 63, No. 2, 81-97 published 1955

The Legend of the Magical Number Seven Nelson Cowan, Candice C. Morey, and Zhijian Chen, University of Missouri

Hick’s Law – Interaction Design Foundation article

Laws of UX – Hick’s Law – Laws of UX website article

What Is Hick’s Law & Why Does It Matter for UX? Anna Fitzgerald – Hubspot blog post – includes the formula to quantify the effect of Hick’s Law